Jio vs TCP

*This is a mirror to the content posted on🚀 Diving into the Network Abyss: Unraveling Jio’s 64kbps Terminal Limit from a TCP Perspective 🌐💻

Hold on to your virtual hats, tech enthusiasts! We’re about to embark on a journey that goes beyond the surface of India’s telecom giant, Reliance Jio. We’re delving into the mysterious realm of Jio’s 64kbps terminal limit, not to dissect Jio but to understand the intricate dance it performs in the world of TCP.

Sure, Jio is a behemoth in the telecom world, with its 5G plans and a game-changing impact on data costs that brought the nation online at lightning speed. But today, we’re not just talking about Jio; we’re on a mission to decode the enigma behind the 64kbps terminal limit, unravelling the threads that make TCP tick in this innovative landscape.

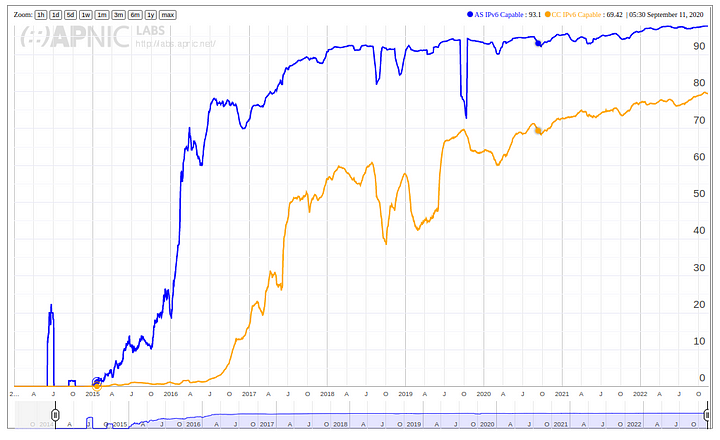

Forget the usual chatter about DAU/MAU numbers; we’re here to explore the techy side of Jio’s prowess. So buckle up, tech explorers, as we venture into the heart of Jio’s network intricacies, where IPv6 adoption reigns supreme at a staggering 92.5%. Let’s push the boundaries of understanding and discover what makes Jio’s TCP perspective truly fascinating! 🚀🔍📡

TCP is arguably the most used internet protocol for data movement from the user’s device to the cloud (HTTP/3 aside). At the moment, HTTP/3 adoption hasn’t been widespread. Even the support for that in Nginx hasn’t been merged.

TCP is a reliable and connection-oriented protocol. It tries its best to get the data from one application on the internet to another. Being so important, it is supported by the whole public internet. TCP has essential features built into it. It takes care that the receiver can handle the data the sender will deliver. It also considers the network bandwidth in how it deals with congestion. During heavy load or artificial traffic shaping by on-route devices, TCP packets can be dropped. However, TCP employs various congestion protocols on either end of the connection to deal with them most efficiently while keeping the network congestion in mind. You can find more details here. The following experiment demonstrates TCP in action on a Jio ISP.

The Experiment

I have a target text file of 1.4 MB (14,45,257 bytes) on my remote server. I am fetching that file using SCP (which uses TCP at the transport layer).

Jio continues to provide data at 64Kbps speed after the unlimited daily usage.

I am trying to Scp this file to and from the server post the daily usage at 64kbps. Note that 64Kbps is 8 KBps.

Results

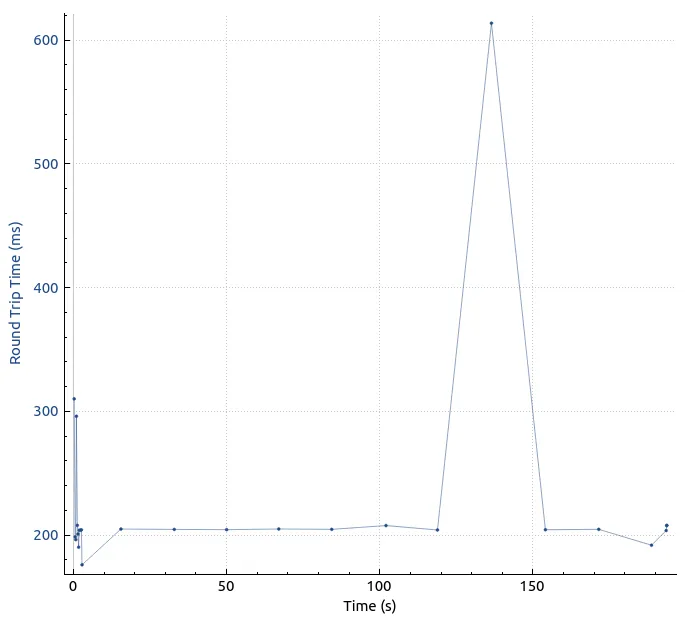

Time vs RTT for download test from the client

From the data above, the RTT usually is about 205 ms, which gives maximum in-flight bytes to be around 1640 bytes for that duration (barely more than the regular 1500 bytes limit for Ethernet frames)

As expected, there will be packet drops somewhere.

To understand the details below, do note that the server’s public IP is 20.203.40.255, and the client’ Jio’s external IP is 47.11.211.102. (I don’t mind sharing these details! Go ahead!)

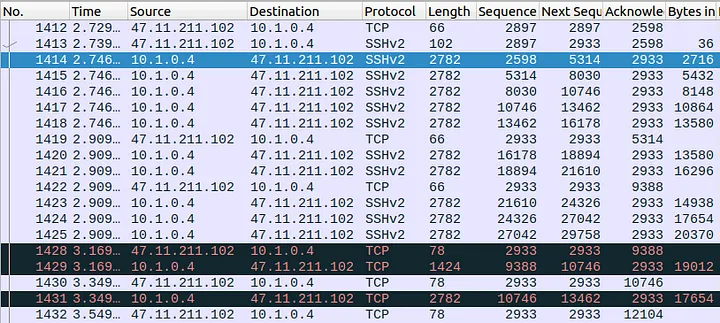

From the server capture, just before the drops,

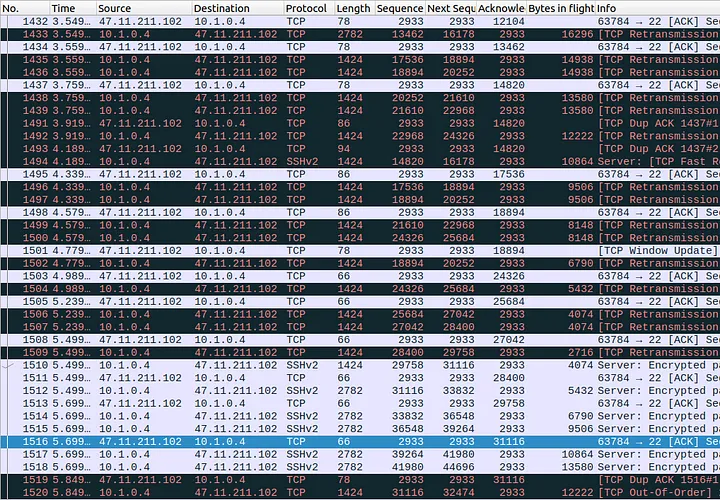

Server Packet logs

On receiving the ACKs from the client (number 1413), the server sends several data packets simultaneously (2782*5 in 1415–1418). This is the TCP congestion protocol in action, expanding the congestion window (CWND). Notice that these individual packets are bigger than possible to pass undropped. However, the MTU for the immediate network on both ends is 1500 and looking at the jumps in the IP identity header, this is probably TCP sending more packets of at most MSS size because of the availability of a higher window.

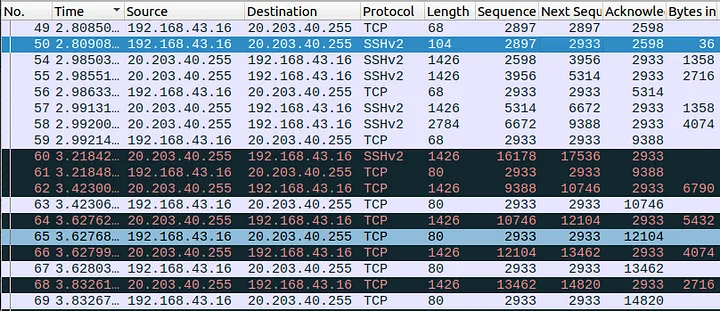

From the client side,

Client packet logs

After sending the ACKs for earlier packets (49–50), we see that it is starting to receive those simultaneous packets. It sends an ACK on 56. And again on 59. Post that, there is no new packet till 3.21s (about 220ms). This indicates that some of the later simultaneously sent packets were dropped. It received packet 60 but not the immediate next ones it was expecting to receive. It sends an ACK back (61) acknowledging this packet but saying there was a packet in between that was not received. Subsequently, the server only sends single TCP frames with the client’s request packets.

This is a duplicate ACK received as the 1428th packet for the server. Henceforth it sends the requested packet again. Notice that these duplicate ACK TCP packets would have dropped the server side CWND and hence must have slowed down in streaming the packets anticipating network congestion.

Server packet logs continued.

Notice the decrease of the bytes in flight. The server then only sends the requested packet segments (which Jio possibly has dropped).

Post packet 1511, it started accelerating again (TCP congestion control at work) but stopped again at 1519.

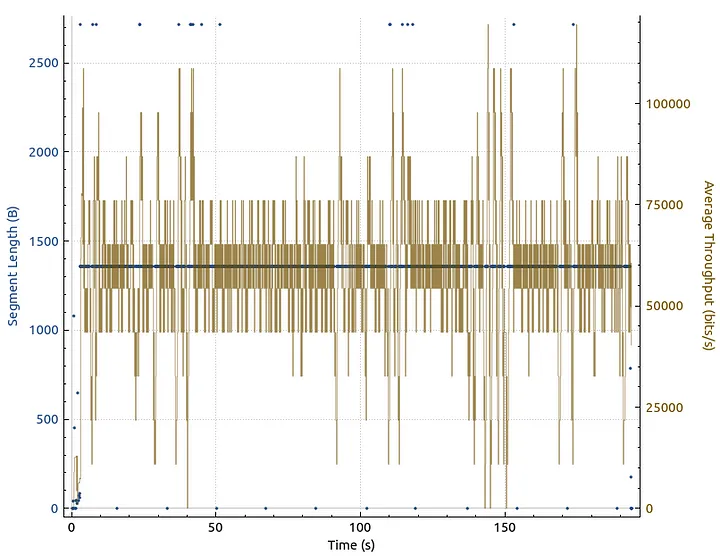

Checking the throughput on Wireshark. This is Jio not letting more than 64000bits pass in a second

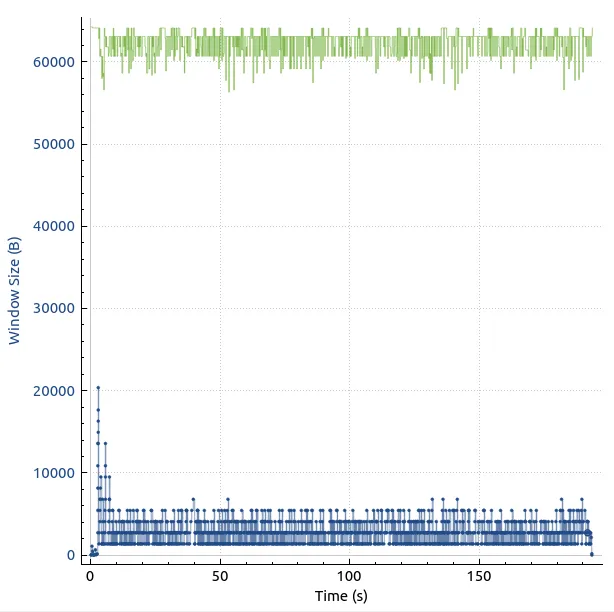

Wireshark Window scaling graph:

Wireshark Window scaling graph:

Server Packet capture TCP Window Scaling on Wireshark

The green line representing the Receive window size stays around the initial negotiated 64128 throughout, while the blue line representing the bytes outstanding is forced to come down to MSS because that’s around what is possible to pass through at the permitted speeds.

Interestingly, there is no ICMP packet recorded on either side notifying of packet drops in the network. It was all about duplicate TCP ACKs and TCP Out-of-Order packets and TCP Previous segment not being received.

The upload traffic test results were similar.

These cycles of increasing bytes in flight and retransmission drop occur continuously throughout the run. This is how TCP copes with packet drops on the network. This is TCP vs Jio in action.

read more...